Washingtonians care a lot about neighborhood names. Just look at the recent backlash over the coining of “North End Shaw,” or listen to how longtime residents feel about “NoMa.” And yet, for all our passion about what to call our communities, few of us know how they got their names in the first place. In part, that’s because so many of them were named in the nineteenth century for now-obscure historical figures. Some are captivating characters worthy of the honor, and some aren’t. Here are DC’s neighborhood namesakes, ranked:

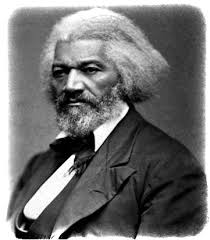

1 Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was the man, one of the great minds in American history, and a living disproof of the prevailing assumption that blacks were intellectually unsuited to function as independent citizens. A slave for the first twenty years of his life, the remarkably erudite Douglass escaped to the North, where his abolitionist writings and orations established him as one of the moral voices of the nation. He lived a righteous life battling injustice, the last 18 years of which were spent in Washington, on a hill in Southwest where his home is now a national historic site. The tiny Douglass neighborhood sits nearby, next to St. Elizabeth’s and the Congress Heights Metro station.

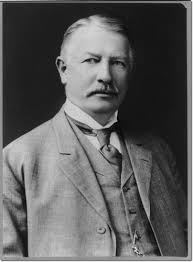

2 Alexander Robey Shepherd

You’ve likely never heard of Shepherd Park or the man for whom it’s named, but I’d argue no one on this list has had a bigger impact on the course of Washington history. The neighborhood is near the District’s northern tip, along the border with Silver Spring. It’s named for Alexander Robey Shepherd (1835-1902), a powerhouse politician known contemporaneously as “Boss Shepherd” and to historians as “The Father of Modern Washington.”

A Gilded Age city boss, Shepherd wielded enormous influence in the 1870s. Before his rule, Washington was a backwater dump with little infrastructure; Congress was considering moving the capital to St. Louis. Shepherd knew this would mean ruin for the District and launched an aggressive program of road, sidewalk, and sewer building that transformed it into a modern city. He ordered the planting of 60,000 trees, installed street lights, and built the city’s first public transportation system (horse-drawn streetcars that would be the envy of DDOT). The capitol stayed put; Washington was saved. Quite a legacy on its own, to say nothing of Shepherd’s passion for equality and civil rights.

Shepherd was an abolitionist who pushed hard for emancipation in Washington, then for suffrage for freed slaves, earning praise and thanks from the likes of Frederick Douglass. Shepherd was incredibly progressive for his era, supporting women’s suffrage, the integration of Washington’s public schools, and Congressional representation for DC. He’s a District hero whose name should probably be found on more than just a sleepy little neighborhood in Northern Washington.

3 Charles C. Glover

Attention confused Washington residents: Glover Park is pronounced like lover, not like clover. Everyone in this city owes a debt of gratitude to its namesake, Charles C. Glover (1846-1936), so the least we could do is get his name right.

Glover was an amateur poet and a benevolent banker who used his vast fortune to beautify Washington. His donations of land and money and his lobbying were instrumental in the creation of treasures like Rock Creek Park, the National Zoo, and the National Arboretum. He was also involved in the building of the National Cathedral, the shaping of the National Mall, and the creation of Embassy Row. As local historian James M. Goode writes: “Few if any native Washingtonians have left a more positive and lasting contribution to the city than Charles C. Glover Sr., who gave of his wealth (before the days of income-tax deductions for philanthropy) to the future public good.” History is silent on how he would feel about Town Hall and Mason Inn.

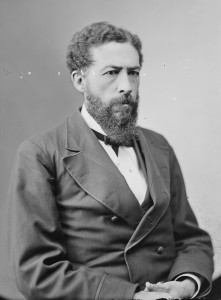

4 John Mercer Langston

The residential Carver Langston neighborhood sits just south of the National Arboretum, on the Anacostia’s west bank. Carver honors George Washington Carver (#7 on this list), while the Langston derives not from celebrated one-time District resident Langston Hughes, but his great uncle, John Mercer Langston (1829-1897). Born a free black in antebellum Virginia, Langston committed his life to fighting for black emancipation, education, and equality. Like his contemporary Frederick Douglass, he was a brilliant renaissance man about The District, taking turns as an activist attorney, educator, diplomat, and politician. Langston helped create Howard University’s law school and served as its first dean. In 1888 he was elected to Congress as Virginia’s first black representative. He absolutely deserves to have his name on a slice of Washington.

5 Robert Gould Shaw

If Shaw, a neighborhood that arose out of freed slave dwellings, had to be named for a white guy with no ties to Washington, it’s fitting that it was Robert Gould Shaw (1837-1863). A lifelong abolitionist, he commanded the first all-black regiment in the Union Army. When he learned that black soldiers were receiving less pay than whites, he joined his men in a refusal of wages until pay was successfully equalized. Shaw died in battle, but his legacy as a champion of equality become the stuff of legend, inspiring thousands of other blacks to enlist. His story was dramatized in the acclaimed 1989 film Glory. Shaw was a good man who would probably think that “North End Shaw” is bullshit.

6 John Tennally

225 years before hungover American University students were shoplifting and peeing on the floor at the Tenleytown Whole Foods, John Tennally was slinging suds to the local drunks at his eponymous tavern, built on roughly the same spot. Tennally’s Tavern was such an institution in the 1790s that the surrounding neighborhood took its name, eventually morphing into the Tenleytown of today, an ironic area known for its lack of taverns. Perhaps, in 200 years, Shaw and U Street will be known as Hiltonville, and H Street will be Englertown.

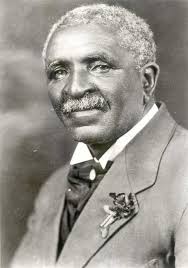

7 George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver (1860-1943), known to Bart Simpson as “the guy who chopped up George Washington,” was a brilliant inventor and botanist heralded for transforming American agriculture and developing over 100 useful products out of peanuts. Time dubbed him the “Black Leonardo.” He’s certainly a deserving namesake, and would be higher on this list if he had any direct connection to the District.

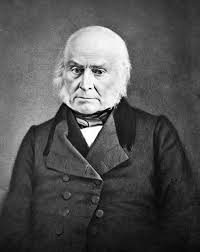

8 John Quincy Adams

Adams Morgan took its name from the unification of two previously-segregated elementary schools named for sixth president John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) and former DC police chief Thomas P. Morgan (#10 on this list). Adams couldn’t accomplish much in his one term as president (Andrew Jackson was a real prick), but he’s considered one of our all-time great statesmen. He negotiated the end of the War of 1812 and, as James Monroe’s Secretary of State, settled America’s northern border with Britain and acquired Florida from Spain (maybe not the best move in retrospect). A clairvoyant opponent of American empire building, he drafted the Monroe Doctrine that dictated non-interventionist foreign policy for generations. And after his presidency he served in Congress and became its most vocal opponent of slavery.

9 Grover Cleveland

The 22nd and 24th president (1837-1908) is one of only a few men on this list to have actually lived in the neighborhood that now bears his name. Our nation’s only three-time popular vote winner bought a farmhouse in present-day Cleveland Park in 1886; he sold it two years later, but the name stuck. Your personal opinion of Cleveland is of course shaped by how you view the Panic of 1893, but regardless, as far as presidents go, the anti-imperialist, corruption-fighting Cleveland was alright.

10 Thomas P. Morgan

The Morgan in Adams Morgan comes from Morgan Elementary, an all-black school that old DC named after a white police chief. Thomas P. Morgan was a big wheel in nineteenth century Washington, an alderman with a steamboat fortune who was tasked with transporting water for the Union during the Civil War. As chief of police, he instituted the District’s first ambulance service, a boon to the city that today transports 18th Street stabbing victims from his eponymous neighborhood.

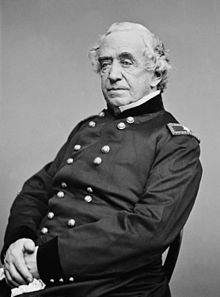

11 Samuel Francis Du Pont

Samuel Francis Du Pont (1803-1865) doesn’t even have a statue in the circle and neighborhood that sports his name; it got moved to Delaware in 1920 and replaced with the current fountain. But he was an important figure in the Civil War, a naval commander who played a major role in securing the Union blockade of the Confederacy that was so crucial to the good guys’ victory.

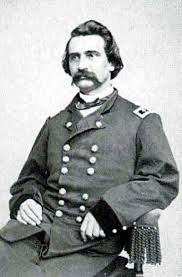

12 John A. Logan

Today John A. Logan (1826-1886) sits atop a horse, quietly watching as the johns and prostitutes of Logan Circle give way to a new generation of ahistorical gentrifiers. He was a congressman from Illinois when the Civil War broke out and he quickly volunteered for duty and fought at Bull Run in 1861. After the battle, he returned to Washington, resigned from Congress, and entered the Union Army as a colonel. Beloved by his men and known as Black Jack for his dark hair and swarthy complexion, Logan rose to the ranks of general, commanding a division under Ulysses Grant during the siege of Vicksburg, where Logan served as military governor upon its capture. He also precedes the likes of Dan Quayle and Sarah Palin as a vice-presidential loser.

13 Joseph Gilbert Totten

Fort Totten was raised to defend Northeast Washington from armed slave-holding traitors during the Civil War. It was named, fittingly, for Joseph Gilbert Totten (1788-1864), one of America’s foremost fort builders. Totten served as the Army’s chief engineer for decades, constructing grand forts across the northeast United States and inventing new methods of military defense. You may recognize him as the author of Brief Observations on Common Mortars, Hydraulic Mortars and Concretes.

14 William Benning

Benning, Benning Road, Benning Ridge, and Benning Heights are named for William Benning, a minor figure who bought a bunch of land around the Anacostia in the 1820s and built one of the first bridges over the river.

15 Joshua Barney

Few have heard of Joshua Barney or the little neighborhood that bears his traffic circle’s name. Barney Circle is a small residential strip along the west bank of the Anacostia; Joshua Barney (1759-1818) was an American naval officer who led a flotilla in the boresome War of 1812. He seems to have been taken prisoner by the British and exchanged on a fairly regular basis, so how good of a commander could he have been?

16 John Roll McLean

McLean Gardens, up by Sidwell Friends off Wisconsin, is a fake neighborhood, a 43-acre housing development built in the 1940s on the site of John Roll McLean’s (1848-1916) former estate. McLean was a rich guy from Cincinnati who owned the Washington Post and a few baseball teams. He built some railroads in Virginia, lost a few elections in Ohio, and faded into history’s mists.

17 Elizabeth Lanier Dunn

Lanier Heights is the only neighborhood in Washington named for a woman, but there’s no great story behind it. Elizabeth Lanier Dunn was the wife of Congressman William Dunn. Together they financed a subdivision and named it Lanier Heights. The End.

18 Thomas Truxton

Truxton Circle is an anachronistic synecdoche, a neighborhood named for a bygone traffic circle that was named for Thomas Truxton (1755-1822), yet another minor American naval commander from the early nineteenth century. He is almost entirely forgotten today, which will happen to you when your most notable achievement is fighting in a fake war nobody’s heard of.

19 Dan Christie Kingman

If you assumed Fort Totten was the only Northeast DC neighborhood named for a former head of the Army Corps of Engineers, you were dead wrong. Kingman Park draws its name from Dan Christie Kingman (1852-1916), who Wikipedia says made “substantial harbor improvements” to the port of Cleveland in the early twentieth century, helping make it the enchanting city it is today.

20 Arthur Randle

Arthur Randle was another real estate developer who built up Southeast Washington in the late nineteenth century for well-to-do white people. He lived in a lavish mansion in present-day Randle Heights nicknamed “The Southeast White House” and reportedly encouraged his fellow plutocrats to build their own mansions on Pennsylvania Ave. SE. He probably wouldn’t like the looks of the neighborhood much these days.

21 George

Georgetown is the oldest settlement in Washington, but historians are unsure who the namesake is. All the options are bad ones. It could be King George II, who reigned when the settlement was established, or it could be George Beall and/or George Gordon, eighteenth century landowners who sold to Maryland what became Georgetown. In those days, everyone was named George.

22 LeDroict Langdon

LeDroit Park is a beautiful Victorian neighborhood that was once the cultural and intellectual hub of black Washington in the early-to-mid twentieth century. But its origins are far uglier. The neighborhood was founded in 1873 by Amzi Barber, a white businessman in the asphalt industry who was on the board of Howard University. Despite its immediate proximity to Howard, LeDroit Park was reportedly developed and marketed as an exclusive, whites-only suburb that included a gate and guards meant to assuage white fears about living so close to so many colored people. Barber named the nascent neighborhood for his father-in-law, LeDroict Langdon (Barber dropped the c), another wealthy white real estate developer.

The whole thing reeks of racial exclusion. There is little written about LeDroict Langdon beyond a number of sources noting him as a real estate developer, so I can’t say for certain what kind of guy he was. But I don’t think it’s going out on much of a limb to say that the rich, white father-in-law of a rich, white guy who created a rich, white suburb is a poor namesake for one of Washington’s proudest historically black neighborhoods. Around 1891, fed up residents of adjacent Howardtown finally tore down the gate separating them from LeDroit Park, and a few years later the first black man moved in, prompting a swift white flight. The name LeDroit remained as it became a black neighborhood, and that’s too bad, because it sounds like Amzi Barber might have been a pretty racist guy, as was the style at the time. At minimum, he’s the lamest namesake in Washington.